Reader Request

I love responding to reader requests, and I recently solicited some questions on my Facebook page.

This question came in from a parent in Pennsylvania, and I think it’s a common issue for gifted kids (and adults, really).

In the interest of full disclosure, I actually have met and adore this child.

His (also gifted) mom writes:

How do you help the gifted child that struggles through incremental learning? For instance, when given a writing assignment, he needs to have it polished in his head before writing it down. Going through outlining, draft, revision, and final edit doesn’t work. But taking extra time to work it through in his head instead of working through typical steps leads to excellent results. Or the child that doesn’t want to learn coding by doing prescribed exercises but can come up (when self-motivated) with a highly complex game of their own devising.

I love this question because it speaks to a core issue for gifted kids.

Gifted doesn’t just mean thinking better: it means thinking differently.

I’m going to respond to this question from two perspectives: the gifted student’s and the teacher’s.

I’ve been both, so this is pretty comfortable for me, and I hope I will represent both perspectives well.

The Gifted Student’s Struggle

If you’re a teacher, one of the most vital things to understand about gifted learners is that they think differently from typical learners. That whole “Do step A, then step B, then step C” thing simply doesn’t work.

It’s like those scenes in A Beautiful Mind where Russell Crowe is thinking and everything is just exploding around him. We can say this about it: It’s not linear.

Or, if you’re a more Benedict Cumberbatch kind of person, Sherlock does it, too.

When a gifted student tries to impose a false order on his/her thinking, it can actually make the thinking make less sense, even to the thinker. It wastes time that could be spent on other pursuits.

It’s frustrating to know that you have the product piece well done, whether it’s a set of math problems or a poster or an essay, and yet you still have to literally go back and pretend you did work you actually didn’t do, at least on paper.

How do you even put the brain’s neural connections into a form others would understand, especially when they look like Russell and Benedicts’?

It makes everything feel like busy work. It makes you feel like your teacher is ridiculous and draconian. (If you’re a student reading this, draconian is not a Harry Potter reference: It’s a historical one. Read about the real, live Draco to learn more.)

It’s frustrating because it’s actually two assignments, rather than one. First, you have the work you actually did, mostly in your head. Then, you have the second part where you write down work you pretend is what you did so your teacher will be happy.

But wait, there’s more!

We haven’t even gotten to the whole “show your work” thing. I’ve written about this before in my article Top Ten Ways to Annoy a Gifted Child, and my colleague Ian Byrd has written about it in his article To Show Or Not To Show (Work).

Why should I have to show my work when the teacher knows I know how to do it? Why should I have to show my work for twenty-five problems when a key benefit of being gifted is that I need fewer repetitions for mastery. I mean, are we just going to pretend all rules of neuroscience are suspended in school? That’s ridiculous.

Neither of these issues are any fun at all. You feel like you’re being punished for being smart.

School becomes a dopamine desert.

It takes something that wasn’t boring and makes it boring.

School begins to feel like a game, and you don’t want to play anymore.

The Teacher’s Struggle

I’ve got some thoughts about this from the teacher perspective.

Thought #1: Teachers aren’t just teaching about now.

We’re teaching for the future, too. Sure, you may be able to write an essay in your head without going through the full writing process now, but I’m not just teaching you for now. I’m teaching you for your future.

Consider this: When you write a peer-reviewed journal article, you can’t just hold that in your head. When you write a manuscript or a book or solve an advanced math problem, you must have defined order or you will not succeed.

When you write a ten-page paper for your college class, you can’t just do that without order, without process. Well you can, but your professor will be able to tell. Trust me on this. As a former English teacher, I can tell you that students always think they don’t need the writing process, and they always, always do better with it. No one’s first draft is the best draft.

I’m not just worried about your now. I need to prepare you. You need practice in the process. You can’t have the first time you really learn the writing process be when you’re on deadline from your publisher (#cautionarytale).

You have to practice now, with things that are easy, so that when you are doing things that are hard, you’re not trying to do the hard thing AND learn a process for it.

Thought #2: Sometimes, the work is about the work, and sometimes it’s not.

With math, sometimes the way your head does it will work for this problem, but it might not work down the road. If you don’t show your work so that I can tell you used a process that will work five years from now, I could be doing you a real disservice.

The deeper you go in your math process (same is true for coding, says my software developer husband), the less the actual answer becomes important, and the more the process itself matters.

On the AP Calculus test, for example, you can just about pass without getting the actual answers to the problems correct. But you will fail for sure if your answer is correct and your process is all wrong.

Sometimes, the teacher needs to see the process to be able to tell where you deviated from the standard method and if that deviation may cause you issues in the future.

Sometimes, any process or method will work, and sometimes it won’t. Your teacher knows, and you sometimes don’t because, by definition, you haven’t done the level of study in this domain that your teacher has.

Thought #3: You have a limit to your working memory.

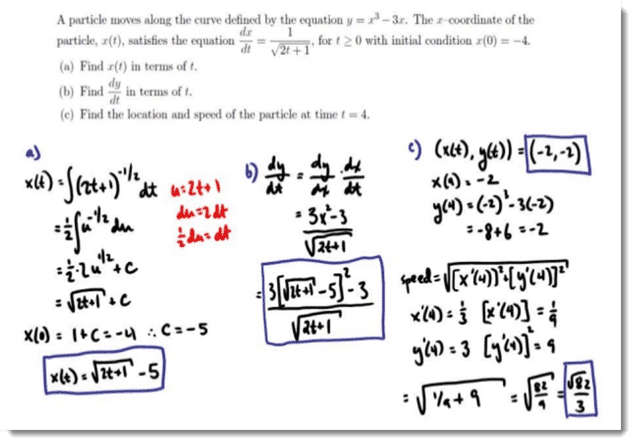

Friend, you’re not doing this puppy in your head:

That’s a question from the AP Calculus BC exam, and it’s coming fer ya.

The working memory has a limit, and it’s a pretty set limit. You can grow it to an extent, but your ability to hold and manipulate vast amounts of material in an organized fashion for the purposes of manipulatin it are insufficient for the tasks you will do in the future.

Thought #4: It’s not just about you.

As we get older, our learning becomes less and less about us. It becomes more and more about how that learning serves others and the general good.

Because of that, we have to make out thinking visible. If we’re going to persuade people of the correctness and usefulness of our ideas, they must be able to see how we arrived at those ideas.

Sometimes, it’s actually written down. When my husband or son (both software developers) write code, they add comments (called – wait for it – “comments”) in the code to tell coders coming after them why they did what they did. It’s not enough that my husband and son are great coders. Their code has to be useful and useable to others.

Sure, your way might work for one thing, but the practice, the exercises, the drafts, the gritty work of work will make your work more valuable, more legitimate, more reliable for others and forever.

Thought #5: It’s a stitch in time.

There’s an old saying that a stitch in time saves nine. You can probably infer it’s meaning: spend a little time now to save a lot of time later.

Practice and exercises and doing the boring stuff now will save you time later.

Let me give you an example. If you don’t know your math facts, you will waste time calculating when you could be manipulating the numbers into something cool. I’m not saying you should memorize them without understanding them, but if you don’t know them, when you get to theoretical math you will be wasting a lot of brain energy (literal energy, real glucose) calculating when you could be thinking.

You practice and show your work now so that you save yourself thinking time later. It’s a favor you’re doing for your future self. You’re welcome.

My Suggestions

- Teachers should carefully consider the following:

- Am I considerate and respectful of my students’ abilities by explaining the rationale of when and why I need incremental learning shown?

- Am I honest with myself about how much is really needed, or do I just have the same system for all students?

- Is the process itself valuable, or is the end result sufficient? Do I really need the student to demonstrate the process to me?

- Am I concerned that the student is getting to the answer in a way that will not work in the future, or am I just concerned about seeing the work now? Have I explained my reasoning?

- Have I seen the student do this type of work or problem before? Can I accept the product in isolation, confident that the student has mastered the correct/needed process?

- Can I explain why I need the work shown/process done to the student in a way that makes sense?

- Can I increase the complexity of the task so that the student realizes he/she must show work/process without it’s feeling fake or like busy work?

- Have I figured out how a student can demonstrate mastery so that I don’t need to keep seeing the same process work over and over?

- When students encounter this dynamic, here are some things that might work:

- Ask to talk with the teacher and discuss it. Be kind. Be respectful. Explain something like this: “I’m noticing that I don’t as much practice as I’m being offered to master the task. I was wondering if there is a way that I can demonstrate that I’ve mastered what you need me to so that I can do it my way/in my head/without showing my work/skipping the exercises/fill-in-current-horror?” If the teacher says no, ask your parent(s) to schedule a conference. Keep going.

- You could share this article, making sure that you don’t do it in an manner that says, “See how wrong you are!” That will backfire.

- Skip a grade. Move your own self along until you encounter work that you actually need practice on.

- Create your own dopamine opportunity by setting micro goals. Set a timer and race yourself. Study how to write an amazing outline online and become a master (there’s real satisfaction to be found in mastering fundamentals).

- Try to grow your resilience in this kind of thing. Look, it’s not going away when you get out of school. You will encounter this same thing in your work and other places as well. Learn mindfulness (find out more on my Emotional Health page), and practice in school. Can you become skilled at experiencing the moment without judgment?

- Understand a key idea: most learners show their work to demonstrate how they got the answer. Gifted learners show their work in an attempt to make their thinking visible and understandable to others.

Thank you so much for the question, and I hope the suggestions and perspectives are helpful. If you have a question, please feel free to ask!